Complete? It isn’t complete yet.

Why Teachers are the Master Masons of the Luxembourg Declaration.

Speaking to Architect magazine in 2013, Jan Utzon, son of Jørn Utzon who designed the Sydney Opera House related a story:

‘My father and I once passed through the great cathedral of Palma in Majorca and were admiring the architecture and all the arrangements in the church. My father asked one of the custodians about when building works commenced. The response was about 1150. My father then asked when it was completed, and the custodian responded, “Complete? It is not complete yet.” They were still working on the building.’

At first, there is a poignancy here. We like to imagine great artists putting down their brush or their pen and stepping back to admire the beauty of their creation. We like to think of things being finished.

Jørn Utzon never got to see the ‘finished’ Opera House. He was forced to resign from the project in 1966 amidst budget disputes and didn’t return to Australia. The Utzon Room, a relatively small and inauspicious part of the complex, is the only interior space designed entirely by him.

But, as he realised in Majorca, architects often have to think generationally and, as Jan Utzon went on to say:

‘My father rationalised that a building like the Sydney Opera House would necessarily be a composite of the ideas of many different people in its lifetime.’

The same is true of Gaudi’s Sagrada Familia. Gaudi died in 1926 and work on the basilica is still ongoing. Indeed, part of the joy of visiting that extraordinary building lies in the knowledge that you are witnessing its creation. It’s hard to imagine a more autographic building and yet the truth is that what we see today is the work of many different architects and craftspeople.

In fact, Utzon wouldn’t have thought of his opera house being ‘complete’, even today when it has hosted thousands of performances. He knew his building would have a life long after his own had ended and, in 2002, wrote a document called the Utzon Design Principles to capture the concepts that had guided his own work and to ensure that the original character might be maintained.

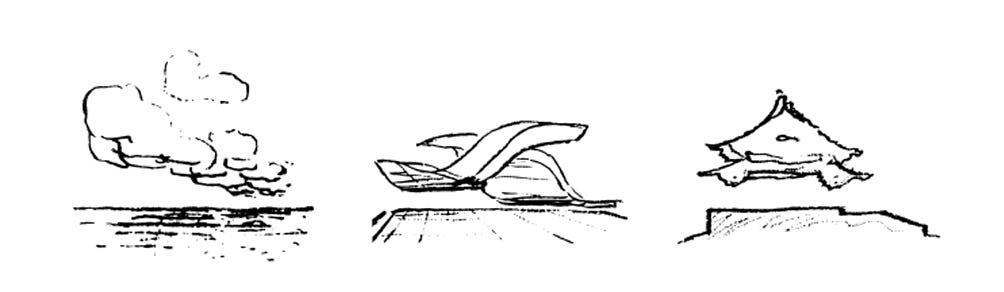

It’s a beautifully written document and, from some of the early sketches that illustrate it, you can see why many considered the opera house ‘unbuildable’ at first.

I don’t claim that the Luxembourg Declaration on Artificial Intelligence and Human Values is as beautiful a document but we can think of it in a similar way: as a blueprint for a grand scheme that seems likely to last for generations and which will be subject to the influence of thousands of creative people along the way. And it is a scheme that is likely to be as important to our descendents as cathedrals were to our ancestors.

I have to admit, I missed the publication of the Luxembourg Declaration earlier this year and only read about it in Kate Devlin’s excellent article in the most recent edition of New Humanist. And, perhaps, therein lies an important difference between the two documents. Despite the reality of its creation, we do associate the Sydney Opera House with a single originator and Utzon’s voice has significance as a result. The same cannot be said for artificial intelligence and so we have many different voices competing to be heard.

Amidst the noise, the Luxembourg Declaration deserves some attention.

It was adopted by the Humanists International General Assembly in July this year, responding to what the organisation describes as “a unique moment in human history” where AI’s rapid advancement offers unprecedented potential for human flourishing but also poses profound risks to freedoms and security.

The document articulates ten principles spanning human judgment, democratic governance, transparency, protection from harm, and shared prosperity, calling upon governments, corporations, civil society, and individuals to adopt these principles through concrete policies and international agreements.

Several principles have clear and urgent governmental applications but we can also apply them directly to educational contexts.

The first, for example, relates to human judgement and states: ‘AI systems have the potential to empower and assist individuals and societies to achieve more in all aspects of human life. But they must never displace human judgment, human reason, human ethics, or human responsibility for our actions.’

I suspect the writers of the declaration had Lethal Autonomous Weapons Systems (LAWS) in mind here but we can use the same principle to think about automatic grading systems. Do they ‘enhance human flourishing’ because they free up time for us to do things we might prefer, or do they displace human judgement and human responsibility? How fundamental is marking work to the educational process?

Item 2 relates to the common good and says: Fundamentally, states must recognise that AI should be a tool to serve humanity rather than enrich a privileged few. The benefits of technological advancement should flow widely throughout society rather than concentrate power and wealth in ever-fewer hands.

I’ve written about the Matthew Effect before and I think it’s one of the most urgent questions we have to face in education. How do we ensure that AI does not disproportionately benefit already privileged students? How do we provide equitable access to devices and how do we upskill teachers in all environments to prevent “digital feudalism”?

Item 7 relates to creators and artists and argues ‘we must continue to recognise and protect the unique value that human artists bring to creative work.’ In a similar way, we might ask how we can teach our students to value their own unique perspectives in a world increasingly dominated by statistical probabilities? As teachers, how do we help them to develop their own voices so they can speak with confidence and reason?

I won’t go through all ten articles in the declaration. You can do that for yourself and, indeed, that is probably the point.

Like the Utzon Design Principles, the Luxembourg Declaration is a document that provides the intent but it has to be applied by skilled practitioners on the ground. Cathedrals and opera houses might need an architect’s blueprint to begin with but they are built by teams of masons and carpenters.

In the same way, educational institutions are built by teachers and students, ensuring that every block of AI-generated content is carved with human intention. And like the Sydney Opera House, this building work cannot wait for perfect plans. It’s already well under way.

As Jørn Utzon notes:

‘We had to commence building at a stage where the working drawings had not yet been completed or finalised, so construction began at the building site a long time before we had completed the drawings, and construction drawings were being produced just ahead of construction as the building grew… This of course is not the best way to do things but on the other hand, if the decision back in the late 1950s had been that the project should have been completed entirely and then sent out for tender, then the Opera House would not have existed today.’